The power of stories in land restoration

Restoring balance. Illustration: Radhika Gupta

This blog is part of a series written by the 2025 participants of the Strategic Communication of Land Restoration Masterclass co-led by UNCCD-G20 GLI and the London School of Economics. Radhika Gupta writes in observance of International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples celebrated every August.

As a visual storyteller working with projects about climate change, mental images are often very vivid for me. Images of places I have been to, and detailed shapes and vibrant colours of the sky, land, forests and faces of the people I have met.

More so, for the places where I have lived and communities with whom I have built relationships through my research and communications work.

Often, it is scenarios of what is possible for such communities that play out clearly in my head. The images are often utopian, because who wants to visualise a disaster? As communicators, we often hold on to hope in our stories – if we can imagine it, we can do it.

So imagine this.

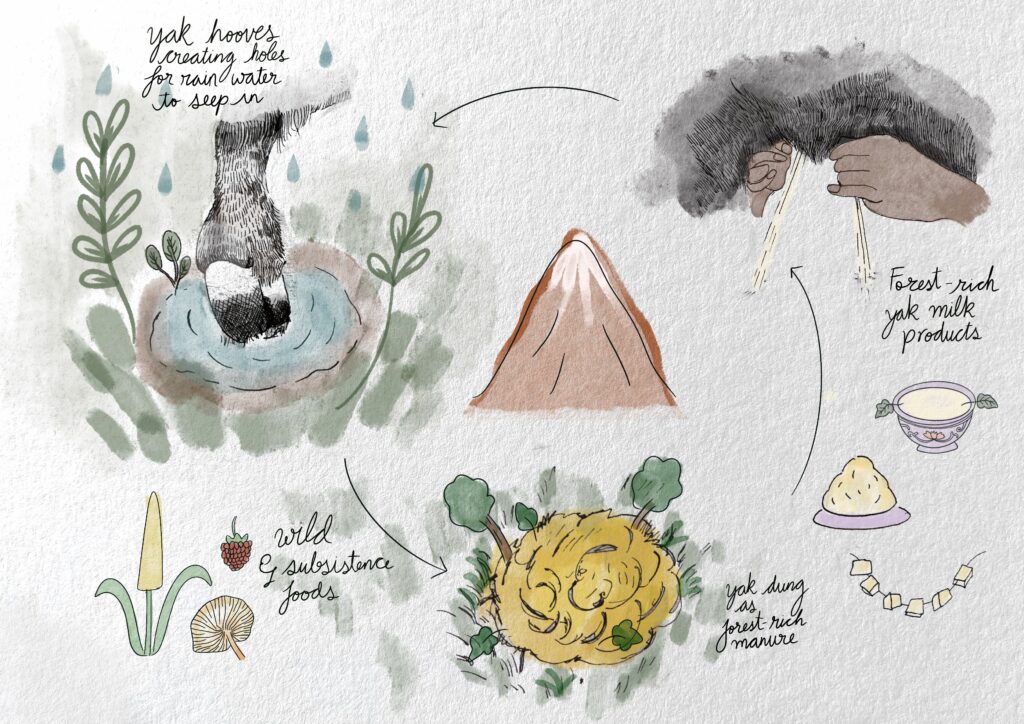

A mountain community in the Himalayas dedicates its time herding yaks at very high altitudes. As the yaks march through pastures, their hooves create holes in the ground making room for rainwater to slowly seep in. Otherwise, the land turns dry and fallow. Meanwhile, the herders rest in ‘goths’ for days and nights and pick wild foods from the forest.

When they track back down to the villages, the yaks bring rich manure from the forest floors, enriching the herders’ kitchen garden and diets. The herder families milk the yaks and make ‘ghee’ and ‘churpi’, providing income in addition to valuable and tasty protein, as yak milk of this quality is rare.

This practice displays the kind of circular economy that supports a balanced ecosystem sustained through generations of indigenous knowledge. This healthy mountain ecosystem is the holder of freshwater in the form of glaciers. It is resilient to landslides, which can destroy downstream lands.

But this has not been the popular narrative about indigenous pastoral communities. Researchers are starting to debunk the popular, yet false, narratives.

They question the practices of pastoralism and cultural burning that were historically portrayed by state policies and dominant narratives as backward and disastrous for forest land. Studies also show this banning or restricting access, often without concrete analysis, giving rise to new challenges. Much of this is driven by colonial mindsets seeking to preserve ‘pristine landscapes’.

While there is a long way to go in undoing the historic harm done to Indigenous Peoples and their lands, changes are taking place. For example, the UN has declared 2026 as the International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists.

Collective storytelling with Indigenous Peoples and local communities can open new avenues and an equal space for dialogue, as shown by If Not Us Then Who?. Co-documentation of intergenerational knowledge can also restore knowledge and restore lands, which can eventually support the diverse diets and livelihoods of high-altitude communities.

The United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues stresses the growing recognition that “advancing Indigenous Peoples’ collective rights to lands, territories and resources not only contributes to their well-being but also to the greater good, by tackling problems such as climate change and the loss of biodiversity.

Those working with land restoration, must continue to ask critical questions. Why, for instance, is capacity building reserved for Indigenous and local communities while ‘knowledge’ and ‘research’ is conducted by an outsider to the community?

New and emerging frameworks, such as the boundary spanner concept, create opportunities for an equal collaborative space between mainstream science and Indigenous Peoples.

Collective storytelling often involves envisioning futures. And utopian visions do not belong to communicators, researchers or development agencies alone. They need to be co-imagined and co-documented with the knowledge holders of those who have restored land for generations.